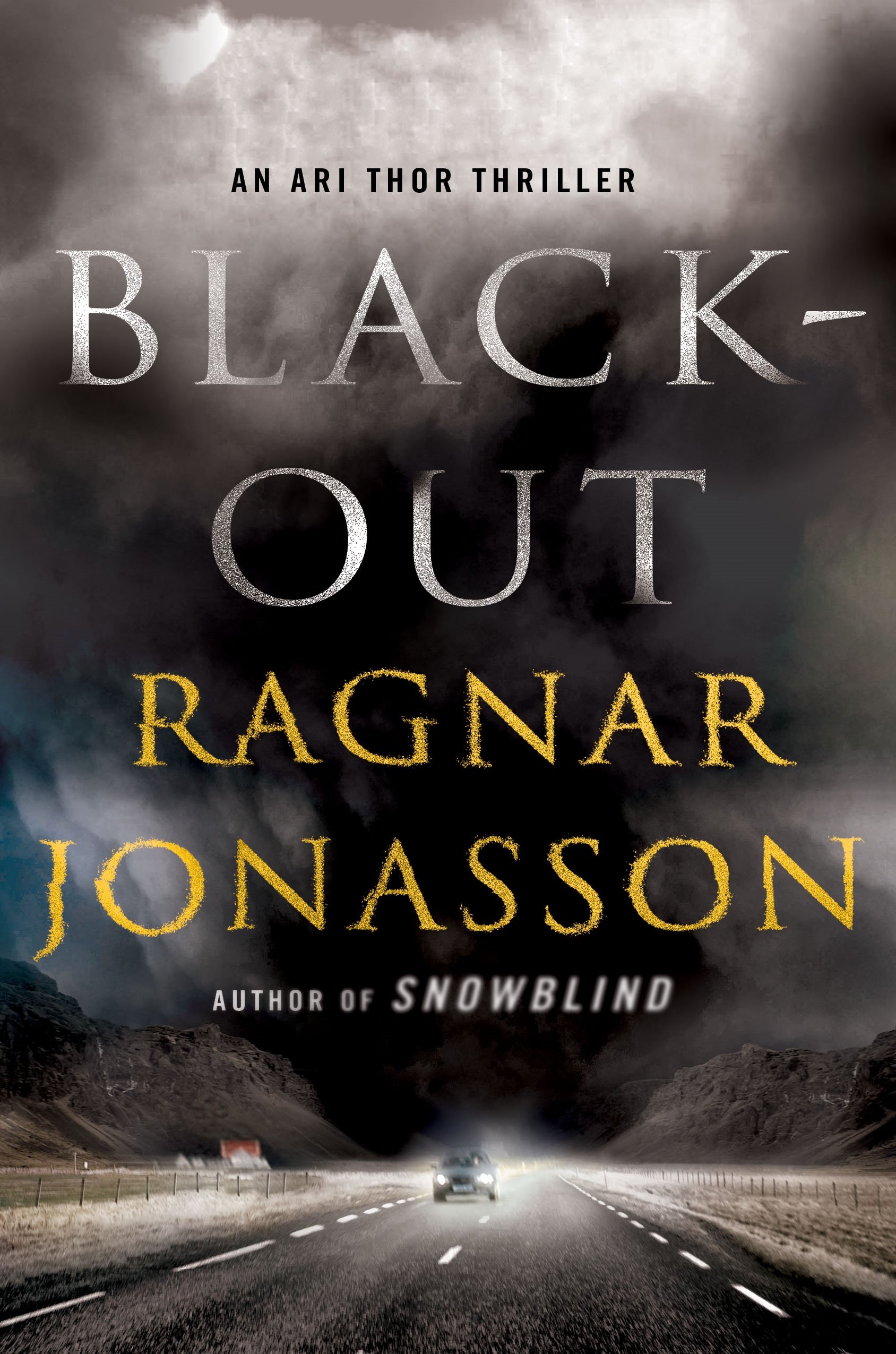

Hailed for combining the darkness of Nordic Noir with classic mystery writing in the tradition of Agatha Christie, author Ragnar Jonasson’s books are haunting, atmospheric, and complex. Blackout, the latest Ari Thór thriller, delivers another dark mystery that is chillingly stunning with its complexity and fluidity.

On the shores of a tranquil fjord in Northern Iceland, a man is brutally beaten to death on a bright summer’s night. As the 24-hour light of the arctic summer is transformed into darkness by an ash cloud from a recent volcanic eruption, a young reporter leaves Reykajvik to investigate on her own, unaware that an innocent person’s life hangs in the balance. Ari Thor Arason and his colleagues on the tiny police force in Siglufjordur struggle with an increasingly perplexing case, while their own serious personal problems push them to the limit.

What secrets does the dead man harbour, and what is the young reporter hiding? As silent, unspoken horrors from the past threaten them all, and the darkness deepens, it’s a race against time to find the killer before someone else dies.

Excerpt: Blackout

Ragnar Jonasson is back with BLACKOUT―the third installment in the Dark Iceland series. I’ve loved this Nordic Noir series so much as Jonasson is a master at penning a mystery that is moody, compelling and totally engrossing (definite Agatha Christie feels).

Ari Thór becomes embroiled in a case that begins when a man is found beaten to death. As it turns out, the victim has ties to the small Icelandic town of Siglufjörður, and the more Ari Thór digs, the more the mystery deepens.

BLACKOUT is not out here in the U.S. until August 28th, but I’m thrilled to give you a sneak peek now!

Chapter 7

News of the corpse’s discovery spread rapidly as one news site after another picked up the story, but none had reported that the victim’s legal address was in Siglufjörður, where life continued as usual.

It was going to be a sunny day, as if the weather had decided that the brutal killing of one of the townspeople was no reason for dropping a few grey clouds into the otherwise perfectly blue summer sky, untroubled by a breath of wind. The news from down south was all about the ash clouds from the eruption that were slowly poisoning Reykjavík, the tainted air brought to the capital by the easterly breeze. No ash from the volcano had reached Siglufjörður as it was too far north. But during the eruption, Ari Thór had heard from a friend of his in town that there were times when ash from volcanoes in the south had fallen over Siglufjörður: once in the nineteenth century and again in the big Katla eruption of 1918, and now people were afraid that the recent eruption of Eyjafjallajökull might wake old and powerful Katla from her century-long sleep.

Ari Thór had arranged to meet Hákon Halldórsson at a coffee house by the small marina. He knew that he was a foreman on the new tunnel that was being constructed between Siglufjörður and neighbouring Héðinsfjörður, as part of the new road link to Akureyri, the nearest large town. Once the construction was finished, the two places, Siglufjörður and Akureyri, would be little more than an hour apart.

The coffee house overlooked the fjord, its deep-blue waters stirring gently in the warm summer breeze, as the brightly painted local boats nodded at their moorings. According to the information Ari Thór had been able to prise from Tómas, who had an encyclopaedic knowledge of the town’s inhabitants, Hákon was best known for having been the singer of a band called the Herring Lads. Their heyday had taken place long after the herring had departed, but they had been quite popular nonetheless, playing at dances around the country and producing three albums. Hákon was no longer a young man, but seemed never to have quite left his pop career behind.

When the weather allowed, he drove around in an antique MG sports car that Ari Thór had noticed on more than one occasion, speculating that its owner might be clinging on to his youth.

Hákon rose to his feet as Ari Thór approached. The MG’s owner was a thickset gentleman with a protruding belly, dressed in jeans and a leather jacket over a knitted sweater, not quite ready to take summer on trust and careful to keep any chill wind at bay. He was short, with grey hair and an unkempt, full grey beard. He shook Ari Thór’s hand firmly.

‘Aren’t you the Reverend?’ he asked cheerfully.

‘No,’ Ari Thór replied with a sigh. ‘My name’s Ari Thór.’

Hákon dropped back into his chair outside the coffee house and waved Ari Thór to sit next to him.

‘Ah, sorry. I was told you’d studied theology. So what’s this all about?’

When he’d called earlier, Ari Thór had only revealed that he needed to talk about one of Hákon’s staff.

‘A body has been found over at Reykjaströnd in Skagafjörður.’

Hákon made no reply, his countenance as rugged and stern as the mountains under which he had been brought up. It would need more than a death to knock him off balance.

‘Haven’t you heard about it?’

‘Well, yes. It was on the news this morning. Was it murder? That’s the impression I got.’ Hákon remained calm. ‘One of my boys?’ he asked finally, and at last there was a tremor of uncertainty in his voice.

‘That’s right,’ Ari Thór said. ‘I have to ask you to keep this confidential. We’re not releasing the name of the deceased right away.’

Hákon nodded, although both he and Ari Thór knew that it wouldn’t be long before the name would become public knowledge, whether Hákon or someone else was the source.

‘His name’s Elías. Elías Freysson.’

‘Elías? Well…’ Hákon was surprised, or at least seemed to be. ‘And I thought he was a good boy.’

‘Good boys can be victims of murder, too.’

‘If you say so,’ Hákon mumbled, almost to himself. ‘Had he been working for you long?’

‘He wasn’t working for me, not strictly speaking,’ Hákon said, almost carelessly. ‘Elías was a self-employed sub-contractor. He’d been working with us in the tunnel for about year and a half. There are … were … four of them: Elías and three boys who work for him. I say boys, but one of them is older than Elías and the others.’

Ari Thór had already dug up all the information he could find about the victim before meeting Hákon. Elías had been thirty-four, unmarried and childless, his legal residence registered as an address in Siglufjörður.

‘I understand he lived here in the town, on Hvanneyrarbraut. Is that right?’ Ari Thór asked, a formality creeping into his voice.

‘Yes, that sounds about right. He rented a place there from Nóra, not far from the swimming pool. I’ve never been there.’

Hákon sipped his coffee.

‘Did he live here most of the time?’

‘Yes, as far as I know. He took on jobs here and there. The latest was some summer house he was working on … in Skagafjörður. Is that where his body was found? Poor bastard.’

There was a new note of sympathy in Hákon’s voice, and for the first time it seemed to have dawned on him that his colleague was dead.

‘I can’t say too much at present,’ Ari Thór said apologetically. ‘Can you give me details of the men who worked with him?’

He tore a page from his notebook and passed it across to Hákon, who wrote down three names, consulted his phone and added three phone numbers.

‘There you go. They’re all decent men.’

Not killers, was the unspoken subtext.

About to stand up, Ari Thór saw that a few passersby had stopped, glancing over to where he sat with Hákon but pretending to admire the little boats at the pontoons or the gleaming cruise liner at the quay. There was no doubt they were wondering why the foreman of the tunnel was chatting to the police. The gossip would start to fly around soon enough.

‘Listen, my friend,’ Hákon added suddenly. ‘That artist guy is the one you ought to be talking to. Those other boys wouldn’t hurt a fly.’

Ari Thór sat up straight in his chair.

‘Listen, my friend,’ he said coolly, his tone measured. ‘You don’t tell me how to do my job…’

Hákon looked up in surprise and hurried to interrupt. ‘Hey.

Sorry…’

‘I don’t care if you used to be some kind of celebrity,’ Ari Thór added. ‘So who’s this artist?’

‘His name’s Jói. I don’t know his full name he’s just called Jói. He’s a performance artist, whatever the hell that is. He’s … you know…’

‘No, I don’t know,’ Ari Thór said and waited patiently for Hákon to stumble across the right word.

‘He’s one of those greens,’ he said, with clear disdain in his voice. ‘He and Elías knew each other?’

‘Yeah, they were cooperating on some charity concert, in Akureyri. Elías was always doing charity stuff. He’s … he was … setting up a concert for the charity that Nóra runs. Household Rescue, you know…’

This time Ari Thór knew exactly what he meant. Household Rescue had been set up in the wake of the financial crash to provide help for families and individuals who had suffered due to the economic situation, people who had seen their jobs disappear or who were simply struggling to make ends meet. The charity had been established as a grass-roots organisation by a group of locals, including a few people in Siglufjörður, and it had started well. Ari Thór himself had donated a few thousand krónur at the beginning, and the organisers were always looking for further support.

‘What kind of cooperation was this? Was Jói planning to do some kind of performance as part of the concert? Was Elías working for Household Rescue?’ Ari Thór immediately regretted asking quite so many questions all at once, a beginner’s mistake in any interrogation.

But Hákon didn’t seem concerned and answered carefully.

‘Let’s see … Elli … Elías, that is, he offered to organise a concert in the spring, with all the proceeds going to Household Rescue. He did all the preparation. Jói sings and plays the guitar as well. He was going to perform at the concert, but they fell out for some reason and that’s all I know about it. So, to put it in a nutshell, Jói’s the man you ought to be asking the questions, rather than Elías’s workmates.’

He smiled broadly.

‘We’ll see.’ Ari Thór stood up. ‘Thanks … my friend.’ He walked swiftly away.

Subscribe for Updates:

by

by