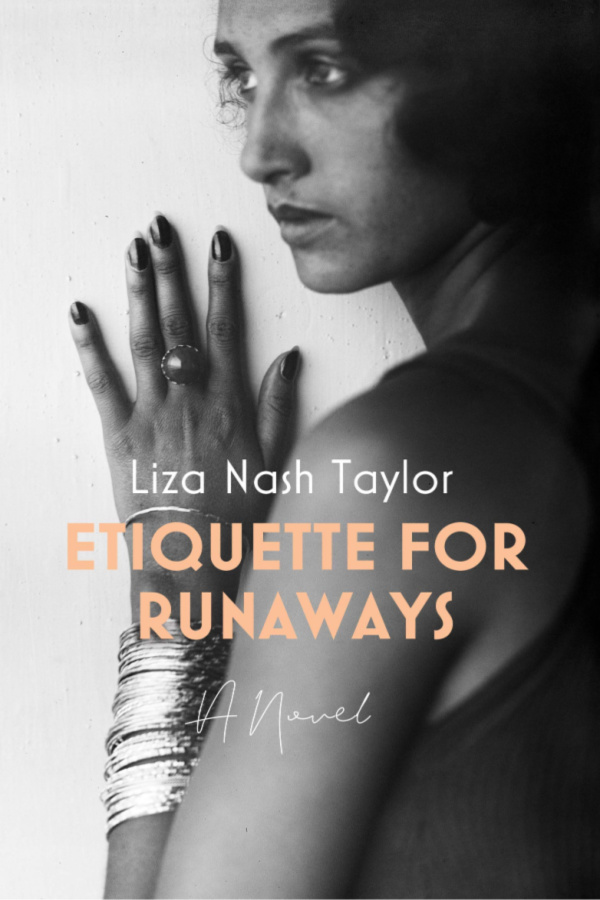

A sweeping Jazz Age tale of regret, ambition, and redemption inspired by true events, including the Great Moonshine Conspiracy Trial of 1935 and Josephine Baker’s 1925 Paris debut in Le Revue Nègre

1924. May Marshall is determined to spend the dog days of summer in self-imposed exile at her father’s farm in Keswick, Virginia. Following a naive dalliance that led to heartbreak and her expulsion from Mary Baldwin College, May returns home with a shameful secret only to find her father’s orchard is now the site of a lucrative moonshining enterprise. Despite warnings from the one man she trusts—her childhood friend Byrd—she joins her father’s illegal business. When authorities close in and her father, Henry, is arrested, May goes on the run.

May arrives in New York City, determined to reinvent herself as May Valentine and succeed on her own terms, following her mother’s footsteps as a costume designer. The Jazz Age city glitters with both opportunity and the darker temptations of cocaine and nightlife. From a start mending sheets at the famed Biltmore Hotel, May falls into a position designing costumes for a newly formed troupe of African American entertainers bound for Paris. Reveling in her good fortune, May will do anything for the chance to go abroad, and the lines between right and wrong begin to blur. When Byrd shows up in New York, intent upon taking May back home, she pushes him, and her past, away.

In Paris, May’s run of luck comes to a screeching halt, spiraling her into darkness as she unravels a painful secret about her past. May must make a choice: surrender to failure and addiction, or face the truth and make amends to those she has wronged. But first, she must find self-forgiveness before she can try to reclaim what her heart craves most.

Excerpt: Etiquette for Runaways

Coming this week is ETIQUETTE FOR RUNAWAYS—a compelling coming-of-age set in post-WWI America, about one woman’s journey as she pursues her dreams, seeks redemption, and paves her own path during a time rife with both temptation and opportunity. I’m thrilled to share an exclusive excerpt from this sweeping novel by Liza Nash Taylor.

The truck clattered back over the long driveway to the house. May hit the first deep rut and bounced on the hard seat. The jolting impact suited her mood. Blossom put her ears back, bracing herself. Shifting gears, May slowed the truck and glanced at the familiar scene in front of her. Beyond the chestnut trees in the yard were hayfields, bordered by rail fence. In the late summer pasture, where hay had been baled, black-and-white-spotted cows stood vivid against yellowing grass. In the background, above her father’s orchards, the mountains loomed a lush, steamy, darker green. Deep within those woods, in a gully that ran along a streambed, Henry Marshall’s still was hidden.

From a distance, the farmhouse appeared much as it did on the canning labels: neat and white, surrounded by boxwood and camellia bushes. May had been six when her mother had drawn the label illustration and she had a distinct memory, as clear as a photograph—her mother, like a flower, in pink linen, sitting in the front field with her sketch pad. As a child, May believed that her mother’s pen had magically repaired the rusted tin roof and sagging porch of the old house, its deft strokes filling in the missing slats of the shutters and reviving the aged, fractured oaks in the yard. A six-year-old could believe in magic, having no idea that such a belief was a luxury of innocence; once extinguished, it could never be rekindled convincingly.

May parked at the back of the house and slammed the truck door. Relief was supplanted by rising indignation. The screened door opened into the kitchen with a rusty complaint and Delphina looked up from the lattice of her piecrust to ask, “Veux-tu déjeuner? ”

May laid the butter beside the sink and responded, “Don’t fret about luncheon for me, thanks.” Her eyes met Delphina’s briefly; she read the concern there. “They didn’t find anything.” The furrows between Delphina’s eyes relaxed.

May walked heavily through the swinging door, then stomped up the stairs. Outside her father’s bedroom, she bent to retrieve the dress she had thrown earlier. It felt heavy in her hand.

She shoved the door open. The handle banged the wall. Odors of liquor and stale sweat blended sourly with hair tonic. Light filtered through the window shade, illuminating faded wallpaper and clothes strewn across the floor. She crossed the room and yanked the shade cord, sending it clattering to the top of the window. Below, in the yard, her mother’s roses were overgrown, tenaciously covering the front wall of the wash house.

“Jesus, little gal, shut the damned shade,” her father said hoarsely, squinting into the flood of sunlight. May turned from the window. His graying hair hung in clumped strands over his forehead. Pushing it back, he propped himself on his elbows. Henry Marshall had been a handsome man in his youth, and May had inherited his strong brows and high cheekbones. But years of sun and bouts of bitter drinking had taken their toll. At forty-eight, he looked ten years older. Blossom nuzzled his hand and he scratched beneath her collar, saying, “Mornin’, girl.”

May moved to the foot of the bed. She hated the tremble in her voice—the constriction of her throat that was the choking of frustration. “It’s afternoon, and guess where I’ve been?” Henry’s head swayed slightly. She stamped her foot, and her voice rose. “Revenue agents came to the Market, with the sheriff. I had no idea you’d been paying him! You said you’d take care of things, didn’t you?” She held the brass rail of the footboard and shook it.

Henry winced, holding up a palm. “Calm down, for Chrissake. They find anything?”

“No, but you weren’t there! You didn’t see how awful that Sheriff Beasley was to Blue.”

“Listen. Blue knows the risks.” May bit her lip. He continued, “I never planned on you being part of this. We were doing fine. You were off at college. I wasn’t expecting you back home so soon.” She stepped back, flushing; stung, as if he’d slapped her. Instantly, she was back in the darkness of disgrace when he ought to be telling her that everything would be all right, that she had saved the day and been brave and clever. Her mouth opened, then closed.

In the shadowed corner behind the wardrobe, Shame leaned against the wall and crossed its arms, nodding, as if to say, Well played, Henry. Well played.

Henry said, “We’ll just have to be a little more careful.”

May’s hands dropped from the bedrail. She raised her chin, working to steady her voice. She spoke quietly. “You’re supposed to be in charge. We didn’t even have a plan. They had guns, Daddy.” Turning stiffly, she walked out, leaving the door open. Blossom followed her across the hall, her nails tapping the floorboards.

For the past twelve years, the door to May’s mother’s bedroom had been kept closed. She turned the door handle and when she went inside, the dog sat at the threshold and would not follow.

The mahogany bed had been brought from New Orleans when Ellen Valentine became Ellen Marshall. Now, the lace net canopy drooped, fogged with dust, and the carved feather fronds and pineapple finials that crowned each post had lost their beeswax sheen. On the dressing table, a silver brush and matching repoussé mirror had blackened with tarnish. The perfume flacon held only a brown stain on the bottom, and when May removed the stopper the residue smelled cloying and rancid. In an oval silver frame, her mother looked young and hopeful in her wedding dress and long pearls, with orange blossoms in her hair. Why aren’t you here, Mama? Parents are supposed to watch out for their children.

Beneath the window, a wheeled, wicker bassinette still stood. May picked up a tarnished rattle from the yellowed blanket. It had been her own, first, and was dented from her teething. Then it had passed on, to baby Henry. She had been so happy to have a little brother. She had promised to behave like a big girl.

But then, her mother had run away. Every time May had tried to ask when she was coming back, her father shook his head and left the room. Eventually, she stopped asking and, at an early age, she learned that the remnants of the Marshall family did not discuss painful subjects. Grief was to be borne with quiet dignity. Anger was not to be expressed in shouting. Love was a stiff hug at birthdays or Christmas, a word to end a letter. It was never declared aloud. In those early days, after her brother died and her mother left, Delphina took over. May spent more and more time with her friend Byrd Craig, who lived next door. Byrd’s parents were warm and kind, not distant and silent as her father was, not always closed away in their room, as her mother had been. Mrs. Craig was generous with her plump-armed hugs that smelled of flowery talcum powder. When Byrd’s older brother, Jimmy, had been killed in France, in the War, May had witnessed the grief his family expressed. Byrd cried openly, and his mother wailed at the memorial service, clutching the triangle of American flag to her breast. The gold star of remembrance still hung in their window.

Since May had come back home in April, she wouldn’t come to the phone when Byrd called her. When he dropped by unannounced, she was distant, refusing to go swimming with him, or riding, or any of the things they had done every summer since they were small. It was as if that girl had ceased to exist.

May laid the rattle back in its place, listening to her father’s careful, heavy tread descending the stairs, then the quiet click of the front screened door as he eased it closed. He would not run the one-woman gauntlet of Delphina’s disapproval by passing through the kitchen. He would slink back in at suppertime, acting like nothing had happened.

From Etiquette for Runaways by Liza Nash Taylor. Used with the permission of the publisher, Blackstone Publishing. Copyright ©2020 by Liza Nash Taylor.

Subscribe for Updates:

by

by

Liza Nash Taylor said:

Hi Vilma,

Thanks so much for featuring my novel this week. I love your blog.