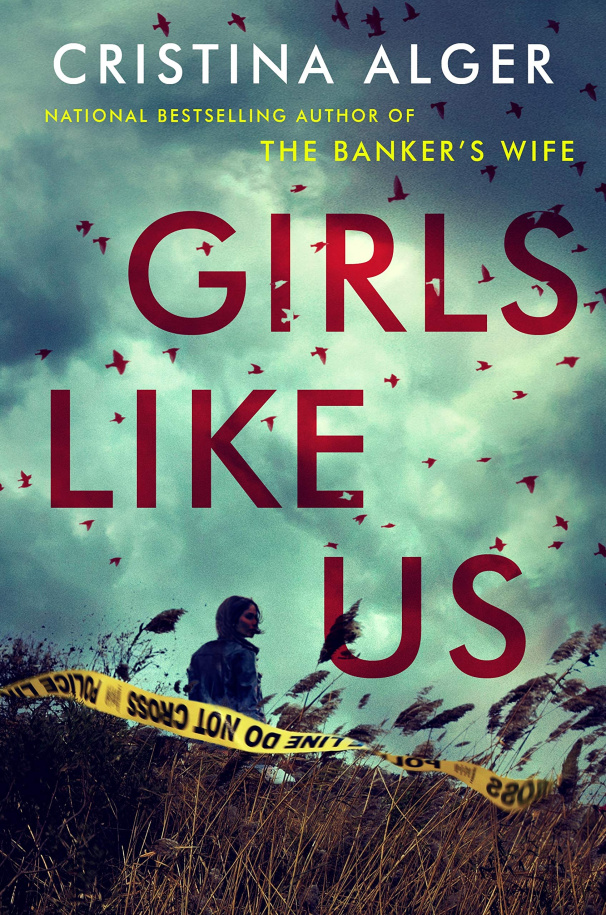

From the celebrated and bestselling author of The Banker’s Wife, worlds collide when an FBI agent investigates a string of grisly murders on Long Island that raises the impossible question: What happens when the primary suspect is your father?

FBI Agent Nell Flynn hasn’t been home in ten years. Nell and her father, Homicide Detective Martin Flynn, have never had much of a relationship. And Suffolk County will always be awash in memories of her mother, Marisol, who was brutally murdered when Nell was just seven.

When Martin Flynn dies in a motorcycle accident, Nell returns to the house she grew up in so that she can spread her father’s ashes and close his estate. At the behest of her father’s partner, Detective Lee Davis, Nell becomes involved in an investigation into the murders of two young women in Suffolk County. The further Nell digs, the more likely it seems to her that her father should be the prime suspect–and that his friends on the police force are covering his tracks. Plagued by doubts about her mother’s murder–and her own role in exonerating her father in that case–Nell can’t help but ask questions about who killed Ria Ruiz and Adriana Marques and why. But she may not like the answers she finds–not just about those she loves, but about herself.

Excerpt: Girls Like Us

From the author of the bestselling THE BANKER’S WIFE comes GIRLS LIKE US — a new, edge-of-your-seat thriller about an FBI agent investigating a string of murders, who in the process discovers her late father may be the prime suspect. Rife with tension and surprises, Cristina Alger’s novel is garnering early critical praise.

While GIRLS LIKE US isn’t out until July 2nd, I’m thrilled to share the first couple chapters below!

1.

On the last Tuesday in September, we scatter my father’s ashes off the coast of Long Island.

Four of us board Glenn Dorsey’s fishing boat with a cooler of Guinness and an urn. We head east, towards Orient Point, where Dad and Dorsey spent their Saturdays fishing for albacore and sea bass. When we reach a quiet spot in Orient Shoal, we drop anchor. Dorsey says a few words about Dad’s loyalty: to his country, his community, his friends, his family. He asks me if I want to say anything. I shake my head no. I can tell the guys think I’m about to cry. The truth is, I don’t have anything to say. I hadn’t seen my father in years. I’m not sad. I’m just numb.

After Dorsey finishes his speech, we bow our heads for a few minutes of respectful silence. Ron Anastas, a Homicide Detective with the Suffolk County Police Department, fights back tears. Vince DaSilva, Dad’s first partner, crosses himself, muttering something about the Holy Spirit under his breath. All three men go to mass every Sunday at St. Agnes in Yaphank. At least, they used to. We did, too. Except for a small handful of weddings, I haven’t stepped inside a church since I left the Island ten years ago. I’m grateful to be outside today. The air inside St. Agnes was always stagnant and suffocating, even after the summer heat subsided. I can still hear the whir of the ancient fan in the back. I can feel the edge of the scrunched-up dollar bill pressed against my sweaty palm, bound for the collection plate. The thought of it makes me squirm.

It’s a calm day. They say a storm is coming, but for now, the sky is clear and cloudless. Dorsey holds the silence for a minute longer than necessary. He clasps his hands in front of him and his lips move as if in prayer. The guys start to get antsy. Vince clears his throat and Ron shifts from one foot to the other. It’s time to get on with it. Dorsey looks up; hands me the urn. I open it. The men look on as my father’s ashes blow away on the wind.

The burial is, I believe, what my father would have wanted. Short and sweet. No standing on ceremony. He is out on the water, the only place he ever seemed at peace. Dad always fidgeted like a schoolboy during mass. We always sat in the back so we could duck out before Communion. Dad claimed to hate the taste of the stale wafers and bad wine. Even then, I knew he was lying. He just didn’t want to confess.

After it’s over, Dorsey hands us each a Guinness and we toast. To the too-short life of Martin Daniel Flynn. Dad had just turned fifty-two when he skidded off the Montauk Highway while riding one of his motorcycles. It was just after two in the morning. I imagine he’d been drinking heavily, though no one dared say as much. No sense in pointing fingers now. According to the Dorsey, Dad’s tires were worn, the road was wet, the fog clouded his visibility. End of story.

With these guys, what Dorsey says goes. Of the four, Dorsey went up the ranks the fastest. He got his gold shield first, then quickly pulled Dad and Ron Anastas out of Plain Clothes and put them into Homicide. When he became Chief of Detectives, Dorsey made sure that Vince DaSilva got elevated to Inspector of the Third. The Third Precinct of Suffolk County covers some of the Island’s rougher parts: Bay Shore, Brentwood, Brightwaters, Islip. It’s where all four men spent their early years together as patrolmen. It’s also where my father met my mother, Marisol Reyes Flynn. Dad always called the Third a war zone. For him especially, it was.

Dorsey and Dad went way back. Our families have been in Suffolk County for three generations. Before that, we hailed from Schull, a small village on Ireland’s rugged southwest coast. They used to joke that we were all probably related somewhere down the line. The men certainly looked it. Both were tall and dark-haired, with green eyes and sharp, inquisitive faces. My father wore his hair in a military crop his whole life. Dorsey, over the years, has had a mustache, sideburns, a shag. But when Dorsey’s hair is short, as it is now, you might mistake him for my father from a distance.

We put out some lines and the guys tell stories about their early days in the Third Precinct. As plain clothes officers, they would show up to work wearing Vans and Led Zeppelin t-shirts. Glory days stuff. They didn’t shave. If they had too much to drink the night before, they didn’t shower. Just rolled out of bed and cruised around in unmarked beater cars, looking for trouble. They never had to look far. In the 3rd, gangs were—and are still—prevalent. Violent crime is high; drugs are everywhere. For all the wealth in Suffolk County, nearly half of the Third Precinct lives at or just above the poverty line. Dad used to say that there was no better training ground for a cop than the Third Precinct, which was why, when you looked at top brass of the Suffolk County Police Department, so many of them came up from out of there.

Dorsey remarks that Dad was the toughest cop in the 3rd, and the best teacher a young patrolman could ask for. The guys nod in ascent. Maybe that’s true. Dad had an unshakeable, almost evangelical sense of right and wrong. But there were contradictions. He loathed smoking and drugs but felt comfortable pickling his liver in scotch. He routinely busted gamblers but hosted a monthly poker game that drew district attorneys and a few well-known judges from around the Island. The criminals he most despised were abusers of women and children, but I once saw him strike my mother so hard across the face that a red outline of his hand was imprinted on her skin. Dad had his own code. I learned early not to second-guess it. At least, not out loud.

Dad’s was a rough sort of justice. He taught lessons you wouldn’t soon forget. Dorsey’s favorite story about Dad was the time he made Anastas lie down on gurney under a sheet at the ME’s office. There was a rookie fresh out of the Academy named Rossi. His dad was a judge and Rossi thought that made him a big shot. He liked to wear designer clothes to work—Armani and Hugo Boss—and that rubbed Dad the wrong way. Dad took Rossi down to the ME’s and had him pull back the sheet. Anastas sat up screaming and Rossi pissed himself, all over his six-hundred-dollar pants. After that, he shopped at JC Penney like everybody else.

Dorsey’s told that story hundred times but he tells it again and we all laugh like we’ve never heard it before. It feels good to remember my father as funny because he was, he really could be. He’d be quiet all night and then pipe up with one perfect, cutting remark. Dorsey and I exchange smiles. I nod, grateful. This is the way I want to remember Dad today. Not for his temper. Not for his sadness. And not for the alcohol, which had finally taken him out on a quiet stretch of wet highway in the early hours of the morning.

Eventually, the sun dips low on the horizon. The sky turns an electric plum-toned blue. Dorsey decides it is time to head home. By the time we pull into the marina in Hampton Bays, night has fallen. We’re carrying well more than our quota of sea bass, but with three cops on board—especially these three cops, who, like my father, were all born and raised and will probably die inside county lines—no one’s going to say squat about fishing limits. These men, Dorsey especially, are the closest thing Hampton Bays has to hometown heroes.

The guys are good and sauced. They talk loudly and repeat themselves and they hug me hard in the parking lot, not once but twice, three times. Anastas invites me to come home for dinner. I beg off, saying I’m tired, I need some time alone to decompress. He seems relieved. Ron has a wife, Shelley, and three kids. He doesn’t need a dour-faced twenty-eight-year-old hanging around his house. DaSilva is in the middle of a divorce. My guess is he’ll head straight to a bar once we’re done here.

After another round of jokes, Anastas and DaSilva stumble off in separate directions. They both drive away in minivans, cars built for booster seats and lacrosse sticks and car pools. Dorsey points to the silver Harley Davidson Sportster that I rode over here. It was Dad’s favorite. He bought it cheap years ago; restored it himself over time. Dad had four motorcycles, or he did, before the accident. Now, I guess, there are three. His babies, he called them. Each one meticulously restored and cared for, swallowing up his off-duty hours like hungry fledgling birds.

“Nice ride.” Dorsey drops his arm around my shoulders and gives me a paternal squeeze. Dorsey married his high school sweetheart. He lost her in a car accident just a few years later. He never did remarry or have kids. Dad made him my godfather, a job he took seriously. All four of my grandparents have passed. Both my parents were, like me, only children. It occurs to me now that Dorsey is the closest thing I’ve got left to family. I feel a pang of sadness. I wish we’d kept in better touch.

“Yeah,” I say, tilting my head against his arm. “It’s a good-looking bike. I miss riding.”

“You don’t have one in D.C.?”

“I’m not there enough to take care of it.”

“You move around with every new case, huh.”

“I’m a great packer. Been living out of a suitcase since the Academy.”

“Your dad was like that. I think that’s why he liked camping so much.”

“He taught me well.” I take a step towards the bike.

“You sure you’re okay to operate heavy machinery? I can give you a lift home if not.”

I wave him off. “Don’t worry about me.”

“It’s dark out. The road might be wet.”

“I’m okay. Really.” I know what he’s thinking. He’s drunk, and I’ve had enough to put me over the limit. I have a wooden leg, though, and unlike my father, I know when it’s time to stop. I never drink the way Dad used to, well past the point of sloppiness. At least, not in public. Like a lot of agents, I save my drinking for the privacy of home.

“You know I always wanted to ride this bike.” I smile, trying to lighten the mood. “Dad used to make me work on it on the weekends but I was too afraid to ask to try it out.” We both laugh.

“Marty loved those bikes of his.”

“He sure did. If there was a fire, I’m pretty sure he would’ve saved them first and come back for me afterwards.”

“Don’t say that.” Dorsey shakes his head, a reprimand. “Your dad loved you more than you know.”

“Do you know what happened to his bike? The one he was riding, I mean.” It’s something I’ve wanted to ask but haven’t quite found the right moment. It seems like a relatively shallow thing to consider, having just lost my father and all. But it’s one of the many small loose ends I know I need to tie up before I leave Suffolk County for good.

Dorsey frowns, thinking. “It went to Impound. I guess it’s still there. I can check.”

“Not the Crime Lab?”

“Nah. Pretty clear it was an accident. I signed the release form for it. Sorry, I didn’t think about getting it to you. It’s basically junk metal now.” He winces, realizing how that sounds. “Sorry. I just meant—”

“I know what you meant. It’s okay. Should I pick it up from Impound, then?”

“I can have them take it to the scrap yard for you if you want. Save you the time.”

“No, it’s fine. I’d like to do it myself.”

“Nell, it’s not salvageable. The bike. It’s pretty badly mangled. I don’t know if you want to see something like that.”

“I’m a big girl. I’ve seen what happens in a fatal crash.”

“I know you have. It’s just different when it’s family.” Dorsey looks away. His eyes are glassy with tears.

I nod, considering. “You’re right. I’ll call Impound tomorrow. Cole Haines still running it?” Cole was an old buddy of my dad’s.

“Yep. Cole will take care of it. I’ll check in on you in the morning.” He watches me straddle the bike. “Listen, did you get in touch with Howie Kidd?”

“Dad’s lawyer? Yeah. He’s dropping by tomorrow, to go through some estate stuff. Glad you reminded me. I’d forgotten about it.”

“You want me there? I can sit with you. Help you go through paperwork.”

“No, no. Thanks. I’m sure it’s all straightforward.”

“Okay. Well, you call if you need anything. That stuff can get overwhelming.”

“Thanks. For everything.” He gives me a two-finger salute and starts to walk away. I rev the engine and he turns back, giving me one final sad smile.

“Hey, hon?”

“Yeah?”

“I love you.”

“I love you, too,” I say, my voice husky. It’s been a long time since I said those words to anyone.

I pull out of the lot before Dorsey does. It feels good to get moving after so many hours on the boat. The cold air puts life back into me. I putter down the Sunrise Highway, across the Ponquogue Bridge, to the house at the end of Dune Road.

It’s my house now, though it’s hard for me to see it that way. It won’t be for long. I need to sell it. I can’t afford to keep it. Even if I could, it doesn’t make sense for me to hold onto it. I haven’t taken a vacation in six years, not since college. I have no use for an old house on the South Fork of Long Island, in a county that holds as many bad memories as good ones.

My grandfather, Darragh Flynn, who I called Pop, built this place back in the 1950’s, when you could still buy a sliver of land with a bay view on a policeman’s salary. Views like this cost a half-million dollars now, maybe more. The house has about as much charm and space as an RV. I know that anyone who to buys it is likely only interested in the land beneath. It is a squat, weather-beaten box with faded grey shingles and cheap sliding doors. Still, it’s not without a certain charm. It has a wraparound deck with view of Shinnecock Bay to the north, and acres of rolling dune grass on either side. I hate thinking about someone bulldozing this patch of marshland just to throw up a McMansion with a pool and a tennis court. I know my father would hate that, too.

I came here a little over a week ago, after Dorsey called me with the news about Dad. I have no return date in mind. As of now, I have no job to go back to. I live in a small walkup apartment in Georgetown that I don’t miss, with an unreliable A/C unit that leaks puddles on the kitchen floor, and the scent of curry wafting up from the Indian place on the ground level. My neighbors are young graduate students, prone to smoking weed and listening to EDM after midnight. Sometimes I can hear them fighting or making love, and when they play music, my walls vibrate from the bass. I think about complaining but I never do. It’s not like I sleep much anyway. When we see each other in the hall, they nod politely and go on their way. I’m certain they know nothing about me. I have to assume that if they knew I was in law enforcement, they might be more discreet about the weed. It’s not their fault. I’m gone for weeks at a time. When I’m home, I come and go at odd hours, leaving for work early in the morning, often returning well past midnight. I have no pets, no plants, no significant other. I can fit most of what I own in a single large duffel bag. I wonder how long it will take for them to notice I am gone. Maybe they never will.

The only person who has called me while I’m here in Suffolk County is Sam Lightman, the head of the Behavioral Analysis Unit and my boss at FBI. Last month, I shot and killed someone in the line of duty. His name was Anton Reznik. He was an associate of Dmitry Novak, one of the Russian mafia’s most profitable traffickers of drugs and women within the United States. Reznik was known to his friends as the Butcher, for obvious reasons. Not someone I will miss. Still, killing a man is never pleasant and this time has been particularly hard on me. For one thing, a bullet nicked my shoulder in the exchange. I was lucky, technically speaking. An inch to the right and it could have opened my brachial artery, almost certainly killing me on the spot. Instead, I traded my badge and my firearm for a couple of stiches, a paid medical leave and the business card of a Bureau-endorsed therapist who specializes in PTSD. By now, the doctors say my shoulder should’ve healed, and it mostly has. It still feels sore now and then, particularly in the evenings, but that’s probably because I haven’t found the time to do physical therapy to rehabilitate the muscles beneath the wound. The Bureau thinks my head should be on straight, too. It isn’t yet. Maybe it never was to begin with.

My father’s death has earned me a reprieve of sorts. “Take the time you need,” Lightman said when I told him, which we both knew meant “as little time as possible.” I can tell Lightman’s patience with my recovery is wearing thin. I’m sure he’s getting pressure from the higher-ups to either put me back in the field or cut me loose. These days, I’ve started to think that the latter is the right thing to do.

I pour myself a stiff glass of Dad’s Macallan and retire to the porch with a wool blanket. I drink quietly and alone, as I imagine he did most nights, until the last streaks of sunset fade and stars light up the sky. I listen to the roar of the ocean and the faint shudder of music from one of the bars across the bay.

It’s over. I will never feel a gravitational pull back here, back home. Not for holidays or for birthdays or for weddings of people I once considered friends but no longer think about. I won’t feel obligated to call my father and I won’t feel guilty when I don’t. I can burn his things; sell this house; never return to Suffolk County again. For the first time in years, I don’t need to medicate myself to sleep. I lie back on the deck couch, put my feet up on the driftwood coffee table. I close my eyes and let the darkness take me.

2.

The cry of a seagull rouses me. My eyes open. It’s light. For a few seconds, I am disoriented. I sit up, startled, and take in my surroundings. The faded grey wood decking. The openness around me. I’d forgotten the singular pleasure of waking up to an endless sky overhead.

The air has an edge to it that it didn’t a few days ago. I pick up the smell of salt and peat and for the first time, something else: firewood. There is smoke coming from a chimney a few doors down. I get up and watch it rise in grey tufts and then dissipate into the slate-colored sky.

Fall has arrived. My favorite season on the Island. The colors fade from vibrant greens and blues to gentler shades of brown and grey. Light dapples the marsh. Just beyond the deck, a snowy egret stands stock-still in a sea of sumac and switch grass. In a flash, the bird dips its beak into the water and retrieves a killifish. The egret cocks its head back and swallows it whole. Then it morphs back into a statue, lying in wait for its next victim. I used to watch them for hours when I was little. I admired their pure white feathers and long, graceful necks. I thought they looked like ballerinas. Pop told me that they almost died out years ago because women so admired their plumage that they killed them and turned them into hats. It broke my little heart to hear that.

Egrets are ruthless killers, too, Pop told me. They know how to extend their wings out while hiding their beaks, fooling small fish into seeking refuge from the sun beneath their shadow. Sometimes, you can see them moving their reed-thin legs in the water in a rhythmic, hypnotic way. It looks as though they are dancing. But really, they are shaking up prey from sediment around their feet. When something moves, they pounce. Knowing this made me feel better. We kill them. They kill small fish in return.

Soon, the waters here will grow cold. The egrets, like the plover and the gulls, will be forced to move further south in order to survive. The change will happen overnight. One day, I’ll wake up and they’ll be gone. When I was a child, I always mourned the day they left. The migration marked the end of the outdoor season, and the beginning of a long winter cooped up in the house with Dad. Winters on Long Island are cold and dark. Most of the folks who stay for it drink more during those hard months, and my father was no exception. I wonder if I’ll still be here when the birds leave this year, or if I, too, will have headed south by then. It’s probably time I start thinking about packing up and moving on. The bite in the air is a good reminder.

I open the sliding door and go back into the house. In the bathroom, I turn on the tap and splash cold water on my face. I fill a glass to the brim and drink it down, trying to offset the effects of drinking too much Scotch on an empty stomach the night before. I stare at my reflection in the mirror. I’ve lost weight. My cheekbones protrude. The hollows around my hazel eyes seem more pronounces. I’ve stopped preparing proper meals. I can’t remember the last time I showered. It’s hard to do it with my shoulder. I fatigue easily, even when washing my hair. The bandaging gets wet and needs to be changed, and that seems like a lot of effort for me these days. It isn’t as though I’m expecting much in the way of company. Still, I am startled by my appearance. I’m not caring for myself. It shows.

I flick on the shower. I need to pull myself together before Howard Kidd stops by this afternoon. There are papers to sign, bank accounts to close. A house to sell and bills to pay. My clothes drop to the tile floor. The tap rumbles and then sputters out water the color of bourbon. Rust. The pipes need replacing. So does the roof, the deck, the dented screen doors. One of the windows blew out in the last hurricane and no one bothered to replace it. My father used to hammer boards over the windows when hurricane season came. Nail marks mar the wood frames. Any broker will tell me to paint over them when I’m ready to sell the house. But I love those marks. As I child, I used to run my hands over them, my fingers feeling out each bump and rivet. They are scars from battles this house has fought and won.

The whole house needs replacing, really. I know that. Maybe there’s no point in painting walls and putting in new screens when, more likely than not, a buyer will tear it all down. Maybe all I need to do is tidy things up so that it looks presentable. Put away personal effects. Remove my father’s hunting trophies: the stag’s head with its glistening, dead eyes. The needle-nosed sailfish arched over the front door. I need to ensure that the air conditioner doesn’t leak and that the fridge stops making that strange, rattling sound that indicates it’s on its last leg. I still haven’t removed my father’s clothes from his bureau. His office door is locked. So is his gun closet. The guns need to go. So does his toothbrush, its frayed bristles hanging downwards off the edge of his sink. My mother’s ashes are probably still stashed in the back of the office closet, in the brass-necked urn which has long since dulled from neglect. I don’t know for sure that the urn is still there, but I bet it is. I haven’t had the heart to check.

I want to pick up Dad’s bike from Impound. If it’s at all restorable, I want to keep it.. If not, I’ll take it to the junkyard myself. It seems like a personal job, something I shouldn’t farm out to Cole Haines. The bike, like my dad, deserves a decent goodbye.

So much administrative work remains. The thought of it all exhausts me. I’ve been ignoring it, hoping it will dissipate, like the fog that hangs over the house in the early morning. But it won’t, of course. There is no one else to do these things but me. The stream of water begins to run clear. I step beneath it. It’s cool, but that’s good. The chill wakes me up, wipes the cobwebs from the drainpipes in my head. The water in this house has always been finicky. My father, a military man at his core, believed in cold showers. As a teenager, I resented him for making me bathe beneath an icy tap. His own showers were two minutes long, maybe three. They always seemed like punishment, as though he was repenting for his sins of the night before. Short, hard, cold showers. He didn’t understand how long it took for a teenage girl to wash her hair, to condition it, to shave her legs. Or maybe he did, but he wanted to punish me, too. I cut off my hair when I was fifteen. Used my own scissors and everything. My father approved. He applauded practicality. He thought blow dryers and curling irons were frivolities, especially for a girl who played sports and didn’t much care what she looked like. He had a point. I’ve worn it short ever since.

I step out of the shower and dry myself off. I fish the last bandage out of the box below the sink and apply it to my shoulder. I slip on my jeans, and a t-shirt, the kind with thumbholes at the hem, so that the sleeves stay in place. I throw on a shoulder harness and over that, an old FBI fleece vest that I borrowed from Lightman and never returned.

From the drawer in the bedside table, I withdraw my Smith & Wesson. It’s my personal weapon, the one I’ve been carrying ever since my Bureau-assigned firearm was confiscated last month. I carry it in my harness, hidden beneath the long sides of the vest. I will continue to do so, at least until Dmitry Novak—the man we were hoping to arrest when I shot Anton Reznik— is in custody. I imagine Novak is unhappy with me for killing his favorite butcher. I won’t be safe until he’s behind bars, and perhaps not even then. With six years at the BAU under my belt, I’ve made plenty of enemies in addition to Novak. Enemies with long memories and violent tempers. I’ll likely always carry a gun. Dad did. He kept an arsenal in the closet of his office, locked of course, and pristinely kept. If he was awake, he was carrying, and if he wasn’t, he was sleeping with a firearm in reach; usually in the drawer of the nightstand next to his bed. It never occurred to him not to. In his world, you were either predator or prey. Egret or killifish.

In the kitchen, I set coffee to brew. I look up the number for the Suffolk County Police Department Impound Lot in Westhampton and dial. I know Cole won’t be there—it’s too early—and I’m happy enough not to have to make conversation about Dad’s passing, what a great cop he was, how I’m doing now. I leave a brief message with my name and cell phone number, saying that I’d like to swing by and pick up my Dad’s bike as soon as possible. I want to do it quickly, without too much fuss. I hope the bike is in one piece, at least. The idea of seeing Dad’s bike torn apart or reduced into scrap makes my stomach twist. In the sober light of morning, I realize Dorsey is right. I may have seen a lot of crime scenes, but everything’s different when it involves family.

As soon as there is enough coffee in the pot, I pour myself a mug and step back out onto the deck. I take one sip before my phone rings. I set my coffee down, check the number. When I see that it’s Sam Lightman, I grit my teeth. After a moment’s pause, I pick up the call.

“Flynn here.”

“How are you doing, Nell?”

“Fucking fantastic.”

“How’s the shoulder?”

“Barely a scratch.”

“And your Dad’s service?”

“Over.”

“Sounds like you’re ready to come home.”

“Are you ready to bring me home?”

Lightman clears his throat, something he does before he delivers bad news. “About that. I talked to Maloney.”

Paul Maloney is the Assistant Director of the Office of Professional Responsibility, an arm of the FBI that I didn’t know existed a month ago and very much hope to never encounter again. After the shooting, Maloney insisted that I undergo counseling with Dr. Ginnis, a psychiatrist kept on retainer by the FBI. Ginnis reports to Maloney, and Maloney has the ultimate say on whether or not I’m fit to work. I get the sense that he’s not inclined to sign off on me unless I do what he tells me to do, and that includes a lot of therapy I’ve been avoiding.

“And?”

“Maloney’s concerned. He said you don’t keep your appointments.”

“I don’t need physical therapy. I feel fine.” I cup my hand over my shoulder, my fingers probing the wound to see if it’s still tender. It is. I stop.

“Not just physical therapy. You need to see Dr. Ginnis, too.”

“I’ve talked to Ginnis.”

“Nell, come on. You can’t go once and call it a day.”

“It’s not my fault I had to leave DC.”

“Of course not. But you could do sessions over the phone. Ginnis needs to write up a full report about your mental fitness. You won’t get a clean eval until then.”

“I get it.”

“We need you back, Nell. I need you back.”

“Are you begging?”

“I would if I thought that would help.”

“Can’t you get Ginnis to sign a form or something? I don’t want to lie on a couch and talk about my childhood.” My voice has a taken on a petulant tone that annoys even me.

“No one has asked you to do that.”

“That’s exactly what he wants me to do. He has an actual couch. I’ve seen it. I lay on it. Once. That was enough for me.”

Lightman chuckles despite himself. “Well, he’s a psychiatrist. They all want a little of that. You might feel better, you know.”

“How about we find the guys who blew off a piece of my shoulder? I’d feel better then.”

“We all would. We’re working on it.”

“Work harder. Or better yet, let me come back to work and I’ll do it for you. I spent eight months hunting Novak. No one is closer to that case than I am.”

Lightman sighs. “I’m worried about you, Nell. You’ve had a hell of a month. I can’t in good conscience send you back into the field on such a dangerous assignment. You know that. You need to take care of yourself. I can get you other names if Ginnis isn’t the right fit.”

“Ginnis is fine.”

“Then talk to him. That’s what he’s there for. You know, Ginnis lost his mom when he was young, too. He was raised on a military base. Just him and his father.”

“So?”

Lightman sighs. “So I think you have some stuff in common.”

“Fine. I’ll talk to him. Don’t expect a miracle.”

“I don’t. I’ll give him your cell number. You can call me, too, you know. I know what it feels like to take a life. It’s brutal, Nell. It stays with you. It can really fuck you up if you aren’t careful.”

I hear the rumble of a car approaching on Dune Road, and then the crackle of tires on the gravel outside the house.

“Thanks for the pep talk. Someone’s here. I gotta go.”

I hang up before Lightman can protest. My hand falls to my firearm. It’s daylight. The driveway isn’t too far from the parking lot for the local beach. Sometimes folks get the two mixed up. Still, I’m not expecting anyone, especially not this early. In my situation, unexpected visitors aren’t exactly welcome.

I hear the gate at the back of the house creak open. I move across the deck and flatten my body against the corner of the house. The wooden shingles press into my shoulder blades. A fly, trapped between the screen door and the window, buzzes overhead. I steady myself, ready my weapon. A rustle of birds shoots up from the dune grass, startled by the visitor. They’re as skittish as I am, and as unaccustomed to guests.

I count the footsteps. Five will take you to the top of the stairs. A tall male figure appears. For a brief second, I panic. From behind, he looks like Dmitry Novak.

My heart rate spikes. My finger grazes the trigger. I step out of the shadows.

I don’t need to say anything; the man raises his hands slowly in surrender. “It’s me, Nell. It’s Lee.” He turns slowly.

When I see his face, I lower my weapon.

“Lee Davis. Jesus Christ. You scared the living shit out of me.”

“Hi, kid.” Lee has always called me kid, even though we’re the same age. I think it has something to do with the fact that he’s a solid foot taller than I am. He moves in and hugs me so hard that I groan in pain.

“What’s wrong?”

“It’s nothing. Just a flesh wound.” I tap my shoulder, feeling the color slowly return to my face. “Lightly grazed by a bullet a month ago. Still a little sore.”

“Lightly grazed. That sounds like something your dad would say.” Lee shoots me a crooked grin. “I’m glad you’re okay.”

“Never better.”

He nods and looks me up and down; I do the same. He hasn’t changed much since our days together at Hampton Bays High School. Tall and thin as a pencil. His shoulders hunch inward, like he can’t quite hear people talking down below. His hair, once jet-black, had a few strands of silver in it now. He probably hates that, but I think it makes him look distinguished. His face, freckled and lineless, is still boyish enough to carry him. He’s handsome in a quiet sort of way that I find appealing. I glance at his ring finger. It’s bare, which surprises me. He always seemed like the sort who’d be driving his kids to soccer games by the time we were in our thirties.

Lee dated nice girls in high school, field hockey players and cheerleaders who smiled a lot and flipped their hair when they laughed. The kind of girl who pretended I didn’t exist. I tried hard to convey that the feeling was mutual, but no one at Hampton Bays High School really cared one way or another what I thought about them. I was just the quiet, skinny girl who wore a black leather jacket to class and was taking college level math by the time I was in ninth grade. The girl whose dad was a Homicide Detective; whose mom was a homicide victim. My mother’s brutal murder was well-publicized in our area. For years afterward, there were whispers about it, about her, about us. Sufficed to say, I was given wide berth at school.

“Sorry about the greeting,” I say, running a hand through my hair. “Occupational hazard.”

Lee waves me off, like a gun in his face first thing in the morning is no big deal. “How was the service? Dorsey said it was nice.”

“It was. What Dad would have wanted, I think.”

Lee gives me a tight smile. I wonder if we should have invited him. A newly minted homicide detective, Lee was Dad’s latest partner. We mostly lost track of each other after high school. I’d heard through the grapevine that he was also living in D.C., attending law school at George Washington. He’d just finished his third year when he found out his mom had Parkinson’s Disease. Moved back to the Island and become a cop. Not unlike my father. Dad was a Marine who managed to knock up my mom while he was home on leave. He did what he thought was right: he married mom and then, when his tour was over, returned home to Suffolk County. They bought a small house with a white fence and Dad joined the SCPD. I always wondered what might have happened to Dad if my mother hadn’t gotten pregnant. My guess is he would have stayed in the military and never looked back.

Lee seems more like a lawyer than a cop. I’m surprised he made it into Homicide. Homicide is a tight-knit group, clubby and exclusive. Lee seems too young and eager to command any respect with that crew. Dad rarely spoke about him and frankly, I’d forgotten they were partners until Dorsey mentioned it last week. Anyway, it didn’t occur to me to invite Lee along and it probably should’ve. Then again, maybe Lee was relieved not to have to spend the afternoon getting wasted with a bunch of weathered, heavy-drinking cops pushing retirement age. He probably does that plenty as it is.

“Can I join you for few?”

“Sure.”

We both sit at the wooden table on the deck. Lee locks his hands behind his head and rocks back in his chair, soaking in the view. A fishing boat glides beneath the Ponquogue Bridge and he watches it until it disappears. His knee bounces nervously beneath the table. It occurs to me that this isn’t a friendly visit. It’s too early in the morning for that, and too soon after dad’s service.

“How long you planning to stick around town?”

“I don’t know. A few more days, anyway.”

“Bureau gave you leave?”

“Something like that.” I feel a ping of impatience. “So what’s up, Lee? I’m guessing you’re not just here to check in on me.”

Lee’s jaw tenses slightly. “Something happened early this morning, out in Shinnecock County Park. A woman walking her dog found a body. A girl, buried in the dunes.”

“That’s too bad.”

“The body was hacked up and wrapped in burlap.”

“Ah.” Our eyes meet. He doesn’t have to elaborate. The previous summer, the body of a seventeen-year-old girl was found in the Pine Barrens, a sprawling, densely wooded preserve in the center of Suffolk County. She’d been dismembered and covered in burlap. It was my father’s case. As far as I knew, he was still working it when he died.

“Same guy, you think?”

“I have to assume so. Or a copycat.”

“ID?”

“Not yet. The vic has a metal plate in her jaw, so that’s something.”

“Any recent Missing Persons?”

“There was a local girl who disappeared around Labor Day. Could be her but we can’t say for sure.”

“Okay.”

“There isn’t much at the office on Pine Barrens. I know your dad kept working on it, though. I was wondering if maybe he kept his own records at home? Notebooks. Laptop. Anything.”

“He had a home office. I haven’t gone in there yet. I was planning to this morning. Howard Kidd’s coming by this afternoon to go through some paperwork. You’re welcome to poke around if you like.”

“That’d be great. Maybe I can stop by later today or tomorrow.” He checks his watch. “I should head back to the crime scene.”

“So that’s it?”

Lee hesitates. “I was hoping I could get you to come with me. Lend a hand with the investigation.”

My shoulder begins to throb, as if to remind me what a shit state I’m in. I cover it with a hand and curl my feet up onto the chair. “Oh, I don’t know. Howie’s coming. I’ve got stuff to do.”

“Howie’s coming when?”

“After lunch, I think he said.”

“Come on, Nell. That’s in like five hours. I promise I’ll have you back in time. We sure could use the help. If this is a serial thing…” He shakes his head, unwilling to finish the sentence.

“Why doesn’t Dorsey call in the FBI? Officially, I mean.”

“Between you and me? Because he’s about to retire and the last thing he wants is mass hysteria over a serial killer in Suffolk County.”

“Maybe a little hysteria is appropriate.”

“Maybe it is. But not on Dorsey’s watch. So no. No FBI. Just you. I’ve already asked him if you could come on as a consultant. No commitment. Just as long as you’re in town.”

“And he was okay with it?”

“He said it was fine, just be quiet about it.”

“How much do I get paid?”

It takes him second to realize that I’m joking. He smiles; a lopsided, embarrassed grin. “Jesus, Flynn. You had me there for a sec.”

I drain my coffee and sigh. It’s not like I have anything else going on. The thought of boxing up our house is unpleasant enough; I’d rather prowl around a crime scene instead. At least I’d have to turn my brain on again for a few hours. Make sure it still works. “Shinnecock County Park East or West?”

“East. Come on. I’ll give you a lift. I’ll even buy you a bagel on the way. You look like you could use it.”

by

by