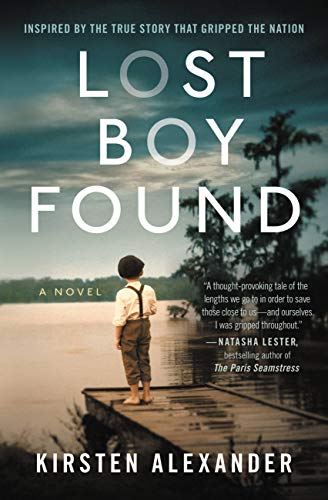

Perfect for fans of the NYT bestseller Sold on a Monday, this Southern historical novel based on the true story of a boy’s mysterious disappearance examines despair, loyalty, and the nature of truth.

In 1913, on a summer’s day at Half Moon Lake, Louisiana, four-year-old Sonny Davenport walks into the woods and never returns.

The boy’s mysterious disappearance from the family’s lake house makes front-page news in their home town of Opelousas. John Henry and Mary Davenport are wealthy and influential, and will do anything to find their son. For two years, the Davenports search across the South, offer increasingly large rewards and struggle not to give in to despair. Then, at the moment when all hope seems lost, the boy is found in the company of a tramp.

But is he truly Sonny Davenport? The circumstances of his discovery raise more questions than answers. And when Grace Mill, an unwed farm worker, travels from Alabama to lay claim to the child, newspapers, townsfolk, even the Davenports’ own friends, take sides.

As the tramp’s kidnapping trial begins, and two desperate mothers fight for ownership of the boy, the people of Opelousas discover that truth is more complicated than they’d ever dreamed.

Excerpt: Lost Boy Found

Coming this week is LOST BOY FOUND — a historical mystery based on the true story of a young boy’s disappearance during the summer of 1913. When two years later a boy is found, two mothers lay claim to him, his disappearance and reappearance bringing up more questions than answers. I’m thrilled to give you a sneak peek into the true story that gripped the nation.

Chapter 1

The three boys bounded through the grass toward the forest, a spray of panicky hoppers glimmering around them, while John Henry recited the passage from Scouting for Boys that approved the adventure. He nodded when he reached the end.

Mary fixed her eyes on the children, one arm raised to block the late-morning sun. “They’ve never gone so far on their own.”

“George wants responsibility.” John Henry smiled at his wife. “We should encourage him.”

“Seven’s no age for responsibility, John.” Nor, she thought, old enough to shepherd a six- and a four-year-old, neither of whom could walk unsupervised to their bedroom at night without veering off to investigate some amusing distraction. An insect, a thud. But she bit her tongue for fear the Scouts had something to say about that, too.

Mary watched her boys slow their pace and enter the forest, lifting their hands and knees as though wading into cold sea. In a blink they were gone, indistinguishable from the dark mess of pine trees, discarded branches and spiky undergrowth.

The Davenport family stayed at Half Moon Lake in July. Their Louisiana lake house was smaller than their home in Opelousas, but still impressive: two stories, pale blue, with slate-gray shutters, white trim, a wide porch and a balcony off the main bedroom. The house sat five hundred yards from the lake, which was fringed on three sides by forest, at the top of a clearing, providing the Davenports a dress circle view and unimpeded access to the water. Here, Mary woke to birdsong and the smell of fresh-baked ginger cake, and later played piano while the drawing-room curtains swelled on the breeze. John Henry took breakfast with his wife, read the St. Landry Clarion, the Atlantic Monthly, Outdoor Life, the latest Picayune, then worked on plans to further expand his business. The Davenport boys—George, Paul and Sonny—watched by Nanny Nelly, spent their days playing cowboys and Indians, chasing dun-colored rabbits, and kicking a ball to one another. In the afternoons, John Henry instructed them in an aspect of Scoutcraft.

This summer day was muggy, but oak trees surrounding the house offered enough shade that John Henry, Mary and their guests, Ira and Gladys Heaton and Gladys’s mother, Mrs. Billingham, would sit outside, as John Henry preferred.

“Perhaps air will ease my headaches. Now that my daughter has declared my homeopathics quackery, I’m left to suffer without relief.” Mrs. Billingham fanned herself.

“You know the pastilles help. There’s no reason to resist every modernity.” Gladys turned to Mary. “Eucalyptus and cocaine. They work wonders.”

“Without any relief at all.”

As the group enjoyed their sweet tea, bees harvested nearby crepe myrtle trees, and hummingbirds flew from foxgloves to hollyhocks in search of nectar.

The Davenport boys had joined the adults for a while that morning, squatting near the woodpile with their toy soldiers—unobserved, Nanny Nelly having been permitted a rare afternoon and evening off to visit her mother—until they’d grown restless and begged to go exploring.

“In search of what?” Mrs. Billingham asked. “Life’s compass,” John Henry replied.

The men discussed business: John Henry’s furniture manufacturing company had sold a thousand chairs in the past eighteen months, and Ira Heaton’s stationery company had secured a significant government contract. Gladys chattered about millinery, bemoaned her rust-red hair, envied Mary’s glossy blackness. Mary worried about the boys. She feigned interest when Gladys, holding up an open copy of the Delineator, said, “Here’s the ribbon I mean,” and offered a sympathetic murmur when Mrs. Billingham confided that the pastilles made her pulse race.

When she went indoors, ostensibly to check with Cook that she’d remembered Mrs. Billingham’s aversion to pepper, Mary shared her concern with her housekeeper, Esmeralda. “What if the boys meet with fire ants, snakes, alligators!”

Esmeralda folded her hands over her dusting cloth. “Mr. Davenport’s taught them how to behave in the outdoors. They won’t come to harm.”

“There’s no behavior that fends off an alligator aside from firing a rifle,” Mary said, though Esmeralda had, as always, calmed her.

At noon—as John Henry led Ira to the library to show him a recently acquired map of Peru, the women strolled in the garden, and John Henry’s butler, Mason, pulled on his boots to go fetch the boys—George and Paul Davenport walked up the hill without their brother.

Mary stopped by the rose bushes. Gladys and Mrs. Billing- ham followed suit.

“George,” Mary said. “Where’s Sonny?” “We thought maybe he’d be here.” “Why would you think that?”

Mrs. Billingham tsked.

“We looked every other place. Shouted and whistled.” “He’s no good at hiding. Except this time. Dropped

Hop though.” Paul held Sonny’s toy rabbit aloft by its threadbare arm.

“I said we’d name him the winner. Only had to show him- self,” George said.

“It’s true, he said that.”

“Where is he, then?” Mary’s voice quickened.

Behind her, Gladys placed her fingertips on her mother’s arm.

“Don’t know.” Paul shrugged.

Mary looked across the grassy expanse and glaring lake to the forest. Nothing moved. She grabbed Paul’s wrist and pushed George’s shoulder to turn him around. “Inside, now.” She called for John Henry as she hurried the boys up the front steps.

Sonny wasn’t in the garden. He wasn’t in the thickets or on the rope swing or in the shed. And though John Henry and Ira scoured the forest and lake’s edge with Mason, they didn’t find the boy.

While the adults searched, George and Paul sat on the porch steps, forbidden by Mary from moving one inch.

“He’s hiding to get us into trouble,” Paul said to Esmeralda. George waved a fly from his face. “You don’t know anything.”

“I know I’m hungry.”

“Hush, both of you.” Esmeralda twisted a tie of her apron until it coiled. “Left your brother out there alone. Should be ashamed of yourselves.”

Mary circled the house, frantic, ran inside to hunt in closets, beneath beds and behind doors, a ring of blackened linen flapping about her ankles. When she knelt on the steps and shook George, demanding he tell her again every word Sonny had said, reducing the boy to tears, Mrs. Billingham insisted Mary lie down.

Esmeralda served ham sandwiches and pastries, made a pot of coffee and, at Gladys’s instruction, added a generous dash of brandy for Mrs. Davenport.

“No, no, no,” Mary said. “No.”

“There’s no cause for alarm,” Mrs. Billingham counseled. “John Henry will find the child.”

But when she could, Mrs. Billingham suggested that Ira drive into town to alert the sheriff.

“The boy’s only been missing a few hours,” Ira said. “He’s probably off frightening small creatures or digging a hole.”

“Digging a hole? Is that what you think children do?” Mrs. Billingham stared meaningfully at the motor car.

Alone in the dark forest, his heart thundering, John Henry looked for signs of his son’s passage: crushed leaves, broken branches, blood.

Subscribe for Updates:

by

by