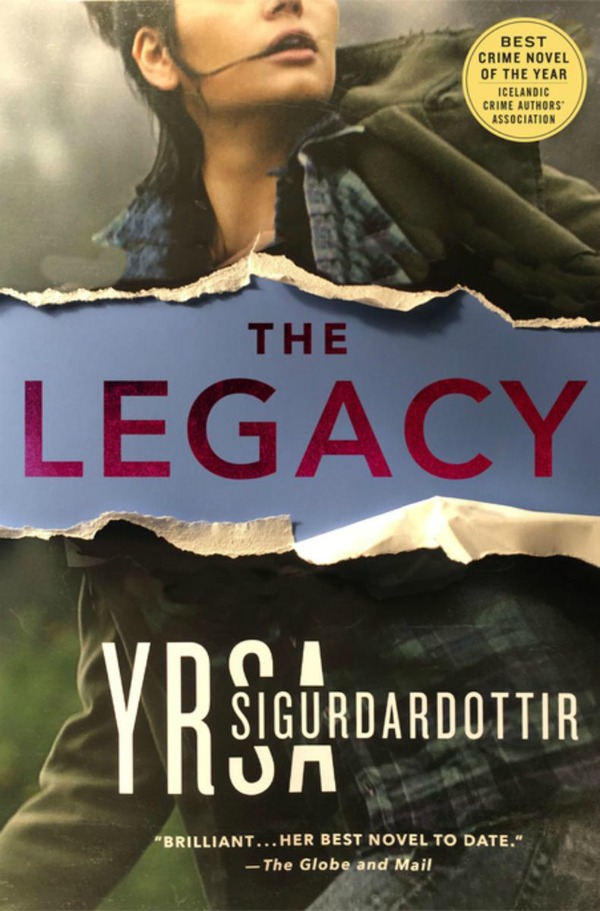

The first in a stunning new series from the author of The Silence of the Sea, winner of the 2015 Petrona Award for best Scandinavian Crime Novel.

The Legacy is the first installment in a fantastic new series featuring the psychologist Freyja and the police officer Huldar.

The only person who might have the answers to a baffling murder case is the victim’s seven-year-old daughter, found hiding in the room where her mother died. And she’s not talking.

Newly-promoted, out of his depth, detective Huldar turns to Freyja for her expertise with traumatized young people. Freyja, who distrusts the police in general and Huldar in particular, isn’t best pleased. But she’s determined to keep little Margret safe.

It may prove tricky. The killer is leaving them strange clues, but can they crack the code? And if they do, will they be next?

Excerpt: The Legacy

I just started this thriller by Icelandic author Yrsa Sigurðardóttir, one which I’ve been so excited to read. It’s out this week, but you can read a sneak peek from this series starter, today!

Thursday

It takes Elísa a moment or two to work out where she is. She’s lying on her side, the duvet tangled between her legs, the pillow creased under her cheek. It’s dark in the room but through the gap in the curtains a star winks at her from the vastness of space. On the other side of the bed the duvet is smooth and flat, the pillow undented. The silence is alien too; for all the times it has kept her lying irritably awake she misses the sound of snoring. And she misses the warmth that radiates from her permanently superheated husband, which requires her to sleep with one leg sticking out from under the covers.

Out of habit she’s adopted that position now, and she’s cold.

As she pulls the duvet over her again she can feel the goose flesh on her legs. It reminds her of when Sigvaldi was on night shifts, only this time she’s not expecting him home in the morning, yawning, hollow-eyed, smelling of the hospital. He won’t be back from the conference for a week. When he kissed her goodbye at the central bus station yesterday he had been more impatient than her to get their farewells over with. If she knows him he’ll come back reeking of new aftershave from duty-free and she’ll have to sleep with her nose in her elbow until she gets used to the smell.

Although she misses him a little, the feeling is mingled with pleasure at the thought of a few days to herself. The prospect of evenings in sole command of the TV remote control; of not having to give in to the superior claims of football matches. Evenings when she can make do with flatbread and cheese for supper and not have to listen to his stomach rumbling for the rest of the night.

But a week’s holiday from her husband has its downsides too; she’ll be alone in charge of their three children, alone to cope with all that entails: waking them, getting them out of bed, dropping them off and picking them up, helping with their homework, keeping them entertained, monitoring their computer use, feeding them, bathing them, brushing their teeth, putting them to bed. Twice a week Margrét has to be taken to ballet and Stefán and Bárdur to karate, and she has to sit through their classes. This is one of her least rewarding tasks, as it forces her to face the fact that her offspring display neither talent for nor enjoyment of these hobbies, although they don’t come cheap. As far as she can tell her kids are bored, never in time with the rest, forever caught out facing the wrong way, gaping in red-cheeked astonishment at the others who always do everything right. Or perhaps it’s the other way round: perhaps her kids are the only ones getting it right.

She waits for her drowsiness to recede, aware of the radio active green glow of the alarm clock on the bedside table. She normally begins the day by hating it, but doesn’t experience the usual longing to fling it across the room as the luminous numbers show that she’s got several more hours to sleep. Her tired brain refuses to calculate exactly how many. A more important question is niggling at her: why has she woken up? To avoid the fluorescent glare of the clock, Elísa turns over, only to choke back a scream when she makes out a dark figure standing by the bed. But it’s only Margrét, her firstborn, the daughter who has always been a little out of step with other children, never really happy. So that’s what woke her.

‘Margrét, sweetie, why aren’t you asleep?’ she asks huskily, peering searchingly into her daughter’s eyes. They appear black in the gloom. The mass of curly hair that frames her pale face is standing on end.

The child clambers over the smooth duvet to Elísa’s side. Bending down she whispers, her hot breath tickling her mother’s ear and smelling faintly of toothpaste. ‘There’s a man in the house.’

Elísa sits up, her heart beating faster, though she knows there’s nothing wrong. ‘You were dreaming, darling. Remember what we talked about? The things you dream about aren’t real. Dreams and reality are two different worlds.’

Ever since she was small, Margrét has suffered from night mares. Her two brothers conk out the moment their heads hit the pillow, like their father, and don’t stir until morning. But the night seldom brings their sister this kind of peace. It’s rare that Elísa and her husband aren’t jolted awake by the girl’s piercing screams. The doctors said she would grow out of it, but that was two years ago and there has been little sign of improvement.

The girl’s wild locks swing to and fro as she shakes her head. ‘I wasn’t asleep. I was awake.’ She’s still whispering and raises her finger to her lips as a sign that her mother should keep her voice down. ‘I went for a wee-wee and saw him. He’s in the sitting room.’

‘We all get muddled sometimes. I know I do—’ Elísa breaks off mid-sentence. ‘Shh . . .’ This is more for her own benefit. There’s no sound from the hallway; she must have imagined it. The door is ajar and she strains her eyes towards it but can’t see anything except darkness. Of course. Who’d be out there, anyway? Their possessions are nothing special and their badly painted house is unlikely to tempt burglars, though their home is one of the few in the street that doesn’t have all its windows marked with stickers advertising a security system.

Margrét bends down to her mother’s ear again. ‘I’m not muddled. There’s a man in the house. I saw him from the hall.’ The girl’s low voice sounds wide awake, betraying no hint of sleepiness or confusion.

Elísa switches on the bedside light and gropes for her mobile phone. Could her alarm clock have stopped? It’s had to put up with all kinds of rough treatment over the years and she’s lost count of the times it’s ended up on the floor. It’s probably not worth putting Margrét back to bed; probably time to start the morning chores, pour out three bowls of buttermilk, shovel over some brown sugar, and hope she’ll be given a chance to rinse the shampoo out of her hair while they’re eating. But the phone’s not on the bedside table or on the floor, though she could have sworn she’d brought it in with her last night before turning off the lights. She wanted it to hand in case Sigvaldi rang in the early hours to let her know he’d arrived safely.

‘What time is it, Margrét?’ The girl has never wanted to be called Magga.

‘I don’t know.’ Margrét peers out into the dark hallway. Then, turning back, she whispers: ‘Who comes round in the middle of the night? It can’t be a nice man.’

‘No. It can’t be anyone at all.’ Elísa can hear how uncon vincing she sounds. What if the child’s right and someone has broken in? She gets out of bed. Her toes curl up as they encounter the icy floor. All she’s got on is one of Sigvaldi’s T-shirts and her bare legs prickle with gooseflesh again. ‘Stay here. I’m going to check on things. When I come back, we won’t have to worry any more and we can go back to sleep. Agreed?’

Margrét nods. She pulls her mother’s duvet up to her eyes. From under it she mutters: ‘Be careful. He’s not a nice man.’

Subscribe for Updates:

You Might Also Like:

by

by